The more distant Estonian history is known

to us through primarily archaeology and,

for example, linguistics. The first in-depth

written documents about Estonian history

date from the Christianisation period in

the thirteenth century, and they were

documented by Christian chroniclers. The Christianisation of Estonian territories

started in the 1180s, and by the end of the

century, it had turned into a holy war. All

Estonians were defeated by 1227, Saaremaa

was the last to fall. It took Estonia almost

seven hundred years from then to become

an independent state. In the meantime,

Estonian territories belonged to German,

Danish, Swedish, Polish, and Russian rulers.

And yet Estonians kept their language and

culture through all that.

Rain in the night. Photo by: Taaniel Malleus / Enterprise Estonia

Another testament

to Estonians’ resilience is perhaps the

fact that today, Estonians are some of the

most non-religious people in the world.

Only a quarter of the population claims to

be religious (most of them Lutherans or

Russian Orthodox).However, this does not

mean that Estonians are purely atheists or

agnostics. It is the organised, church-driven

religion that seems alien to them; on a

personal level, Estonians’ beliefs are often

linked to nature, spirituality, or folk tradition.

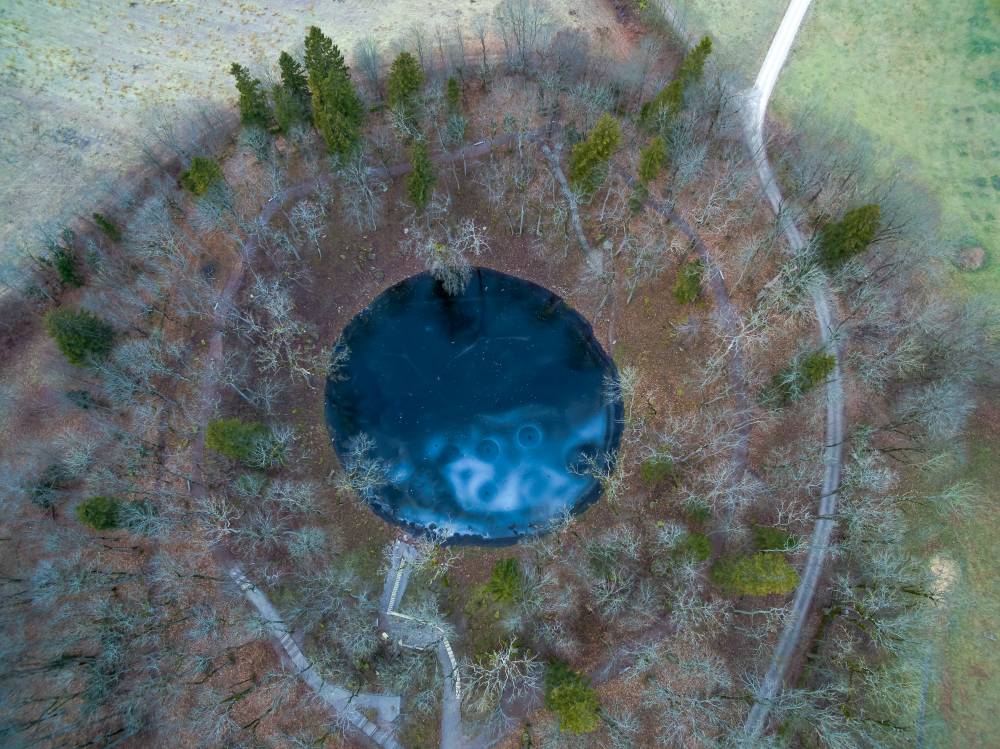

Viru bog in the Northern Estonia. Photo by: Siiri Kumari / Enterprise Estonia

BACK TO ALL QUESTIONS